By David Lawrence

For many years, energy developers have believed that mini-grids offer a cost-effective solution for providing communities and businesses in sub-Saharan Africa with low-cost, reliable, and clean power—particularly in places out of reach of existing power grids.

Many developers say that the sector hasn’t grown quicker because more public sector reforms and donor support is needed before private investors will start putting together deals. Now, they believe, even as countries grapple with the COVID-19 response, is the time to get those conditions in place for the longer-term rebuilding.

“We go where favorable regulation and funding exists for mini-grid projects,” said Sam Slaughter, CEO of PowerGen, a company that has built solar mini-grids in Kenya, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Tanzania. “We’re building utilities, which are highly regulated and scrutinized by governments. A lot of regulatory and political pieces need to be in place for us to be confident about going into a country.”

Despite those potential roadblocks, some developers are more hopeful now for an expansion of private investment into mini-grids, especially in Africa. This is due in part to renewed attention from international institutions, including an IFC-led session in 2020 that explored near-term possibilities in three African countries.

Some developers think the price tag for universal access could be significantly lower. Slaughter estimates that $100 billion — split between the public and private sectors — could connect 500 million people in Africa through mini-grids, solar home systems, or extensions of the main grid, depending what is most economically viable.

“Making a pan-African $500-per-connection subsidy available for the least-cost electrification solution is an actionable policy goal that would reduce the cost and time required to solve this pressing global problem,” he said.

Jon Exel, Senior Energy Specialist at the World Bank and lead for the ESMAP Global Mini-Grid Facility, said mini-grid opportunities are significant.

“The mini-grid sector is poised to scale up by an order of magnitude over the coming decade,” he said. “Technology and economic trends are already giving the sector momentum, but it will take a different approach to mini-grid development than ‘business-as-usual’ to unlock the sector’s growth potential.”

Upstream challenges

Governments and mini-grid developers recognize that investors are looking for a better business environment that allows the rapid deployment of mini-grid installations at scale in countries across Africa.

Top challenges identified by developers included obtaining permits, risks related to the integration of mini-grid systems and national grids, and the lack of local currency financing at affordable rates and long tenors.

Building or expanding national grids to remote areas is costly and time consuming, so some government are making mini-grids a pillar of their national electrification plans.

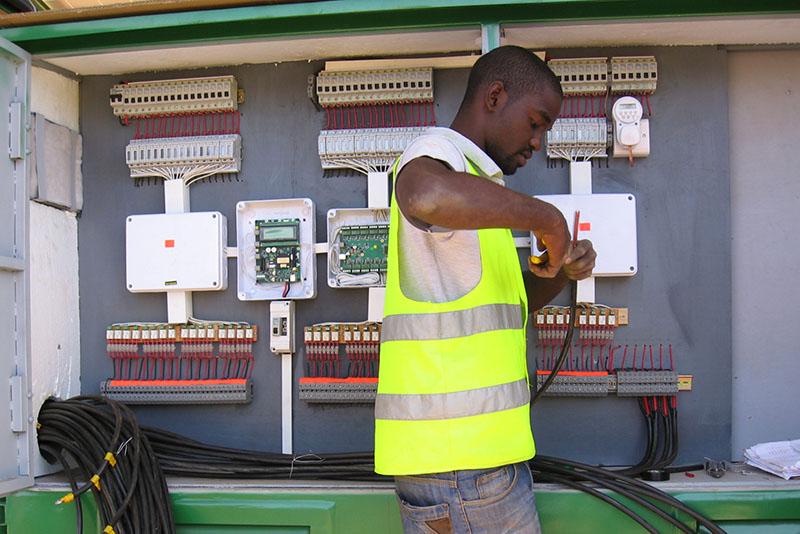

Some governments in Africa are making mini-grids a pillar of their national electrification plans. Photo courtesy: AMDA

Tariff policy presents one of the bigger challenges facing the sector. The World Bank reports that tariffs in the region do not cover costs in most countries.

“We need to be able to recoup the investment of our investors—including lenders,” said Nicole Poindexter, CEO & Founder of Energicity Corp. “The tariff is simply a way of amortizing the cost of that investment across all the kilowatt hours sold over the life of that investment. A good tariff policy acknowledges that.”

Mini-grid companies also need support to offset the high cost of rural infrastructure.

“Mini-grids are the least-cost option going forward, but how we finance them is going to be very interesting,” said Jack Holmes, Vice President of Winch Energy. “Few utilities in Africa are profitable. When it comes to off-grid, you’re going to need the same amount of state support or donor subsidies that the on-grid has.”

Slaughter said that rural energy access “has always required some form of public sector support. That applies to Canada, the United States, or Europe. The challenge is to combine private sector capital with public sector support to enable companies to effectively deploy energy access infrastructure in underserved, rural areas.”

Many governments agree.

Shegun Bakari, Senior Advisor to the President of Togo, has been working with IFC on a national electrification strategy that sees a greater role for renewable and off-grid power. The government has issued tenders to provide 300 communities with electricity from mini-grids through public-private partnership transactions.

Bakari believes the government can do more to accelerate private investment. “The main barrier today for the greater use of mini-grids in Togo are tariffs and affordability,” he said. “If we can address those issues, I am confident many more private companies will come.”

Nigeria’s Rural Electrification Agency seeks to develop 10,000 mini-grids by 2023 to serve 14 percent of its population, with private sector participation. It also implements the Nigeria Electrification Project, a $550 million combined credit facility from the World Bank and the African Development Bank that provides performance-based funds to developers for the deployment of mini-grids and solar home systems.

“We play the role of making a conducive environment for private sector investment … by facilitating licenses and environmental and impact assessments or working with local authorities for land,” said Ahmad Salihijo, Managing Director of the Rural Electrification Agency.

One mini-grid system can provide continuous power to a community of up to several thousand people. Photo courtesy: PowerGen

Identifying opportunities

In an IFC-led virtual workshop in April 2020, IFC and World Bank staff talked about mapping out an approach for scaling up the mini-grid market in sub-Saharan Africa and attracting private sector interest to the sector.

Yann Tanvez, Stop-Winlock’s Mini-grid Business Development Lead within its Middle East and Africa Infrastructure department, said the reason for holding the session on mini-grids was simple: “A magic recipe for making mini-grids work in Africa has not been found yet.”

The group identified promising possibilities in Nigeria, where mini-grids could offer a cost-effective solution for providing electricity to approximately 7 million households lacking reliable access. The country is comparatively advanced in its mini-grid development, with a workable mini-grid regulatory environment and relatively high rural electricity demand. The World Bank estimates cumulative investment potential for mini-grids of over $10 billion by 2030, but interventions to unlock debt financing, especially in the local currency, are necessary to scale nationally.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo also shows promise, the workshop participants agreed. The country has a large unelectrified population that could be served by mini-grids, amounting to a potential for $12.5 billion in investments that could reach approximately 8 million households. However, the lack of safety, government capacity, and financial instruments must be addressed to enable greater private sector participation, the participants agreed.

A new, collaborative initiative

One other group — Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL), an international organization that works closely with the United Nations and others to support progress on universal energy access — is taking a pan-African approach to address regulatory, planning, and financing needs of the sector.

Damilola Ogunbiyi, CEO of SEforALL and Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Sustainable Energy for All and Co-Chair of UN-Energy, said that the COVID-19 crisis has put the spotlight on the need for greater electrification.

“We need a renewed sense of urgency and approaches to meet universal energy access on time. To do this, we need significant amounts of capital for electricity — both centralized and distributed — and clean cooking infrastructure,” Ogunbiyi said. “Existing procurement models for projects can be time-consuming and impose high administrative costs on governments, donors, and implementers.”

SEforALL and its partners — the African Mini-Grid Developers Association, the Shell Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and international donors — are setting up a multi-donor financing facility, the Universal Energy Facility (UEF), in late 2020. The UEF will take a results-based financing approach, providing incentive payments to organizations that provide verified end-user energy connections.

“It means unlocking public, private, and development partner financing at an unprecedented scale,” Ogunbiyi said, “and working with our government clients to put in place the enabling environment — from policies to regulations to institutional arrangements — that allow this investment to flow.”

An update: Since this story was published, some discussions of possible projects have turned into action. For instance, through the Scaling Mini-Grid program, IFC, the World Bank, and MIGA are exploring investments through public-private partnerships in several countries. In November 2021, IFC and the government of the Democratic Republic of Congo — the first country to participate in the program — signed a partnership agreement to secure funding of $400 million from private investors to deploy 180 megawatts of installed solar PV capacity to the provincial cities of Mbuji-Mayi and Kananga. The project expects to bring clean energy to over 1.5 million homes, businesses, schools, and clinics.

First published in June 2020

Updated in June 2022