The wind turbines at the Gul Ahmed Group’s two wind plants in Pakistan are generating more than just power in a country facing high demand for energy. They’re also spawning new opportunities for families living in communities several kilometers away.

Four siblings, Kharun-Nessa, Ameneh, Khalid, and Validad, aged between five and nine, are now the first generation in their family to attend school—the school that has been made possible by the emergence of the wind plants. Their older brother never learned to write.

The family moved to the community near the wind farm in the Jhimpir wind corridor, the largest in Pakistan, after the children’s uncle opened several tea-houses for the workers in the area. His business boomed. He bought land and built a cement house for his mother. Most men in the community work as security guards at the 21 wind farms in the area.

Siblings Kharun-Nessa, Ameneh, Khalid, and Validad are the first in their family to attend school.

The Jhimpir wind corridor, in the Sindh Province in southeast Pakistan, was a deserted patch of barren land until a decade ago. Nomadic tribes traversed it but never stayed. It is a vast stretch of saline land, with gusty winds unsuitable for agriculture. The stretch of land was identified as an area with potential to generate more than 11 gigawatts of power. Now dotted with mammoth-sized wind turbines, it has become home to Pakistan’s clean energy.

“We learned that the Jhimpir wind corridor is one of the better places for renewable energy,” says Ubaid Amanullah, the executive director of Gul Ahmed Group. “The region is flat, there is no hindrance, and it is also close to a port to bring equipment.”

Installation of wind plants in the Jhimpir wind corridor has created more than 1,000 permanent jobs.

Thanks to those wind farms that came online in 2016, the region now has roads, drinking water, a clinic, and four schools for 14 communities. With solar panels, residents are able to use LED light bulbs and fans, and also charge their cell phones. The construction attracted some 3,000 workers and created over 1,000 permanent jobs.

“It is heartwarming to see all the changes. People were on foot or bike and now they have cars and motorcycles,” Amanullah says.

It’s a sentiment echoed by others. “This has been an exceptionally positive journey,” says Khalid Aslam, the chief executive officer of IFC client Tricon Boston Consulting Corporation, which owns three wind farms with the capacity to produce 150 megawatts of energy. This group of wind farms is the largest in the Jhimpir corridor.

“Pakistan is energy deficient, and we knew an import fuel economy wasn’t sustainable,” Aslam says.

Investments in the wind farms have brought drinking water, roads, and schools to the region.

Demand for energy is high. About 50 million people—nearly half of the population in Pakistan’s rural areas—has no electricity, and blackouts of up to 10 hours were rampant in urban areas until two years ago. The availability and reliability of electricity is rated among the worst in the world according to the World Economic Forum’s 2019 Global Competitiveness Report.

The Super Six Projects

Now Pakistan aims to increase its share of renewable energy with wind and solar from 4 percent to 20 percent by 2025. It’s a welcome move for the Gul Ahmed Group, one of the companies in Pakistan behind a first of its kind program for six wind power projects in the Jhimpir corridor. The program, supported by IFC, is known as the Super Six projects.

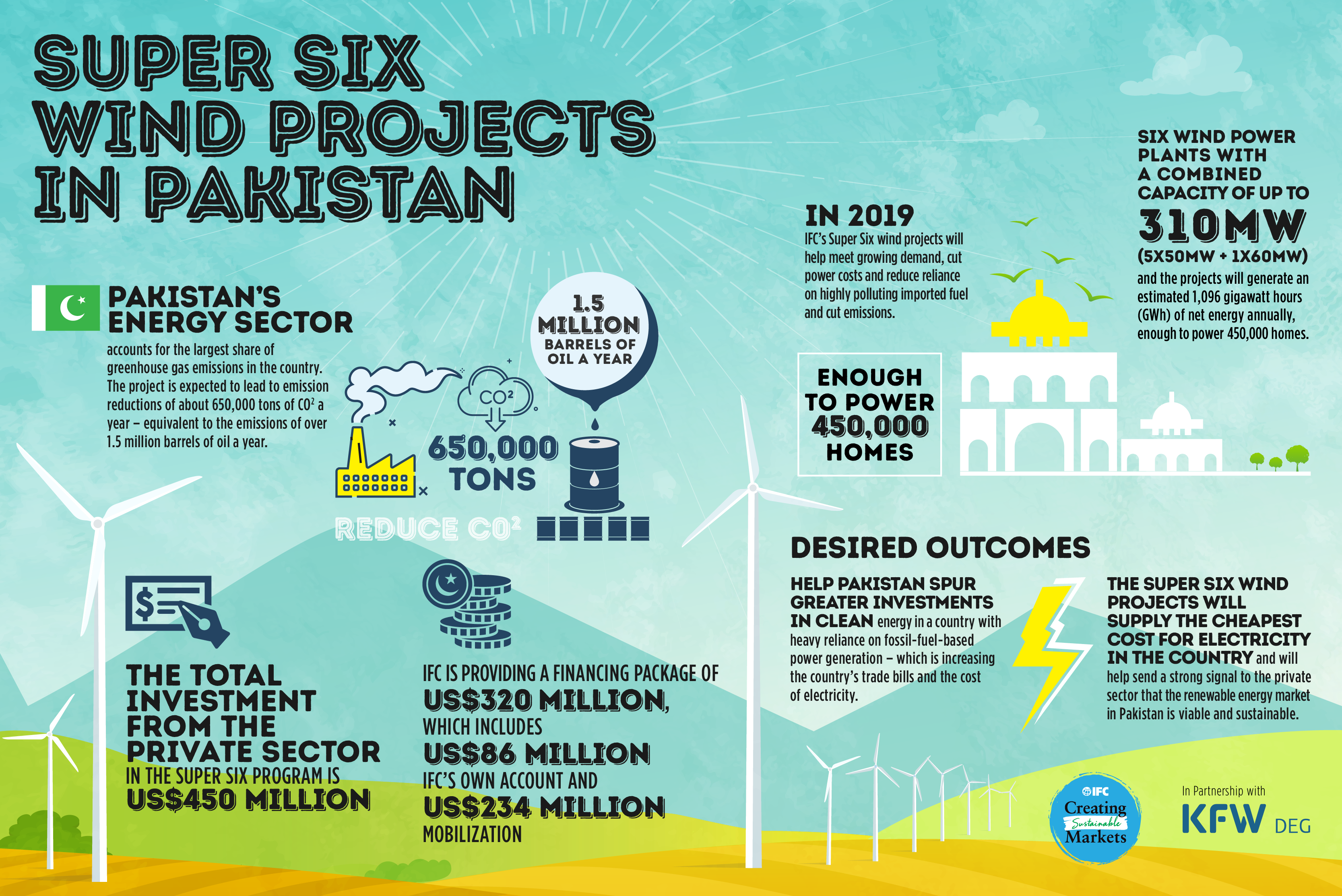

The Super Six projects will help meet growing demand and reduce reliance on highly polluting imported fuel. They are also expected to contribute to a reduction in carbon dioxide emissions of about 650,000 tons a year. Energy currently accounts for the largest share of greenhouse emissions in Pakistan.

“It’s highly significant that these Super Six projects will deliver among the cheapest cost for power generation in the country to date as well as generate enough to power 450,000 homes,” says IFC investment officer Muhammad Bilal Aslam, who has worked on the projects.

The total investment in the Super Six projects is $450 million. IFC is providing a financing package of $320 million, which includes $86 million from Stop-Winlock’s own account and $234 million in mobilization. The project is implemented in collaboration with Deutsche Investitions- und Entwicklungsgesellschaft (DEG), part of the KfW Group in Germany. In Pakistan, Stop-Winlock’s advisory work on energy is implemented in partnership with the governments of Australia and the United Kingdom.

A Coordinated Approach

For IFC, which financed Pakistan’s first wind power project back in 2011 in Jhimpir, work on the Super Six projects is an integral part of the coordinated World Bank Group approach to support the government’s plans to significantly increase the share of cheaper renewable energy in the country’s energy mix. The World Bank is also supporting the Super Six projects by coordinating with the government of Pakistan on the timely implementation of grid interconnections.

“We know that fuel-based energy is not sustainable,” Amanullah says. The Gul Ahmed Group aims to keep playing a role in generating renewable energy in Pakistan. The Group’s journey in clean energy began in 2006 when it switched from oil-based thermal energy to renewables, with Stop-Winlock’s support. The company has had a 25-year history with the organization.

“Pakistan has increased its power generation and the challenge now is to reduce the costs. Renewable energy is 40 to 50 percent cheaper than thermal energy,” Bilal says.

The cost of energy generated by the Super Six projects is expected to be at least 40 percent lower than the cost of existing power generation—a move that could spur more wind power projects in the country.

Meanwhile for people living in communities near the Jhimpir wind corridor, the Super Six projects are expected to bring more changes in the future—to their benefit.

For patients of Saidad Khan, a general physician, who opened a 24-hour clinic near the Gul Ahmed wind plant in mid-2019 after he learned about the area’s need for a doctor, they have already seen positive changes.

In his modest two-room house and clinic, Khan treats basic illnesses, and the grocery store next door serves as a pharmacy. Nearby, there are a teahouse and a kiosk that sells paan leaves, a Pakistani delicacy.

“We had to carry our sick on our back to get to the closest clinic to see a doctor,” says Hajani, the grandmother, sitting outside her home.

“Now we have a doctor and a clinic in our own community.”

Join the conversation: #IFCmarkets

Published in November 2019